Artifact #3: Multimodal Research Project

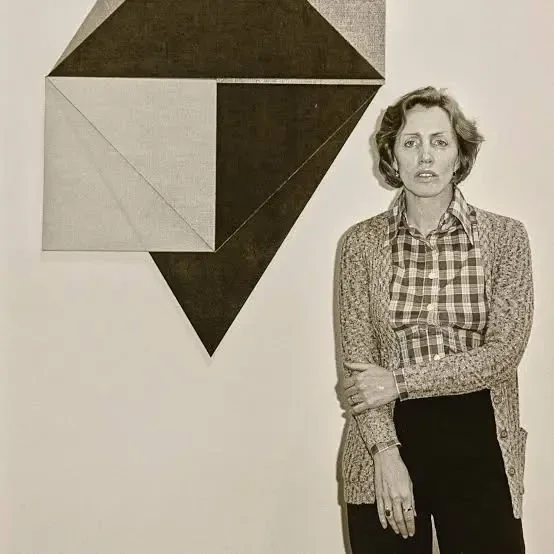

On Fire Engine Red (1967) by Dorothea Rockburne

WHAT DO YOU SEE?

Fire Engine Red (1967) by Dorothea Rockburne

When you look at Fire Engine Red (1967) by Dorothea Rockburne, you see a stark, almost confrontational dialogue between two elemental forms and two distinct surfaces. The entire field is dominated by the coarse, brown texture of the raw, unprimed canvas, whose woven, organic grit feels more like a wall or a piece of industrial cardboard than a traditional painted ground. This is not a painted color but the exposed foundation of the artwork itself, a tactile and earthy plane that absorbs light. Set against this neutral, absorbent field are two shapes in a flat, uniform red so specific it justifies its titular warning: the urgent, high-gloss hue of a fire engine. This color possesses a visual alarmism, a synthetic intensity that sits starkly against the natural, muted brown.

On the left, a tall, vertical rectangle stands, but it is subtly tilted, its axis refusing to align perfectly with the canvas edge, which gives it a sense of dynamic instability rather than solid, architectural certainty. Its color is not a painted layer but a solid, opaque plane, a slab of pure signal. The edges of this rectangle are crisp yet soft, hinting at the artist's hand rather than a machine's precision. To the right, a massive, hand-drawn circle dominates the space. This is not a mechanically perfect circle; its slightly irregular, looping outline reveals the human gesture at work, making it feel more like a planetary body or a forcefully drawn orbit than a geometric ideal. The relationship between these forms is one of tense interaction. The circle aggressively overlaps the rectangle's edge, and, more dramatically, its own perimeter is brutally cropped by the right edge of the canvas, as if its energy is too immense to be contained by the picture plane.

This creates a powerful push-and-pull across the surface; the rectangle acts as a tilting anchor of weight, while the circle is an active, expansive force. As Michael Brenson suggests, Rockburne’s work engages the “five senses of the mind,” and here, the industrial clarity of the forms is constantly complicated by the primal feel of the canvas and the human imperfection of the drawing (Brenson 9). The composition feels less like a static arrangement and more like a snapshot of a collision—a moment of intense visual alarm frozen in time. The painting’s power derives from this sustained tension: between the systematic and the intuitive, the industrial and the organic, the intellectual concept and the sensory experience.

The Big Ideas

Fire Engine Red uses the formal language of 1960s Minimalism not to create an impersonal object, but to stage a tense and powerful dialogue between systematic order and intuitive human expression. To understand this, one must see the painting against the backdrop of its time. As art historian William C. Agee outlines, the 1960s New York art scene was defined by a decisive "shift from the personal, romantic vision of Abstract Expressionism toward a new sensibility that was hard-edged, impersonal, and object-oriented" (Agee 52). This was the era of Minimalism, which embraced a "new aesthetic of the industrial and the systematic" as a central tenet (Agee 55). Rockburne’s painting immediately engages with this zeitgeist through its reductive forms, uniform, industrial color, and large scale.

However, Rockburne simultaneously subverts these very principles. The painting’s title, Fire Engine Red, anchors it in the world of functional, urgent objects, yet the execution is deeply human. The raw, textured canvas provides a primal, tactile ground that is the antithesis of Minimalism’s smooth, industrial finishes. The titular red forms, while flat, are defined by their imperfect, hand-drawn edges and dynamic placement. The circle is not a perfect geometric specimen but an energetic, hand-painted orbit; the rectangle is not statically placed but tilts precariously. Most dramatically, the circle’s breach of the canvas boundary is an act of compositional rebellion against the self-contained, "object-like" nature of much Minimalist art.

This is not a rejection of system but an enrichment of it. Rockburne’s own words perfectly articulate this central idea. She described her core interest as creating “systems that have a human element” (Rockburne and Bui). This statement is the key to unlocking Fire Engine Red. The painting is a system—of color, form, and scale—but it is one invigorated by gesture, intuition, and material truth. It stands as a critical and enduring statement that argues for a more sensory and humanistic form of abstraction, proving that intellectual rigor does not require the suppression of the hand, but can be powerfully amplified by it.

A multimodal project by Paul Rowe

for Dr. Sturm's ENGL 1102 course.

Georgia State University, Fall 2025.

Work Cited

Agee, William C. "The Sixties: A New Decade." The Park Avenue Cubists: Gallatin, Morris, Frelinghuysen and Shaw, Grey Art Gallery, 2002, pp. 49-63.

Brenson, Michael. "Dorothea Rockburne: The Five Senses of the Mind." Dorothea Rockburne: The Five Senses of the Mind, Grey Art Gallery & Study Center, New York University, 1988, pp. 7-21.

Rockburne, Dorothea, and Phong Bui. "Dorothea Rockburne in Conversation with Phong Bui." The Brooklyn Rail, 4 Mar. 2009, brooklynrail.org/2009/03/art/dorothea-rockburne-with-phong-bui.

Create Your Own Website With Webador